Unfinished Agenda: U.S. Disengagement from West Asia

While the disengagement of the US from West Asian affairs has propelled the regional states to pursue diplomatic interactions on their own, it would be much too early to suggest that the region will become a bastion of peace and tranquillity any time soon. Many of the sharp competitions and rivalries that have defined the region for several decades such as between Saudi Arabia and Iran-- viewed in several instances as of “existential” concern for the countries concerned — remain resonant.

This week, a consummate former diplomat Talmiz Ahmad who has served in the Middle East talks of the fresh dialogue and the new alignments across the region

Ever since President Joe Biden entered the White House, he has signalled a fatigue relating to matters pertaining to West Asia and to focus his attention on coping with the challenges posed by a rising and increasingly assertive China. Thus, neither the revival of the nuclear agreement with Iran nor US policy relating to Afghanistan commanded his immediate attention, though both matters had been expected to be priority concerns for him.

The US’ inglorious departure from Afghanistan after twenty years of war and the handover of the country to America’s enemies, coupled with the failure to attain its strategic objectives in Iraq, Syria and Libya, mark a nadir in the US’ standing across West Asia and the loss of its credibility as the principal role-player in regional affairs.

As Biden’s fatigue with West Asia brings down the curtain on the influence of the hegemon, West Asia’s states have discovered both the need for and the freedom to initiate interactions with friends and enemies without the looming direction and intervention of the global superpower. West Asia is now going through a new era in regional diplomatic activity.

Diplomatic churn

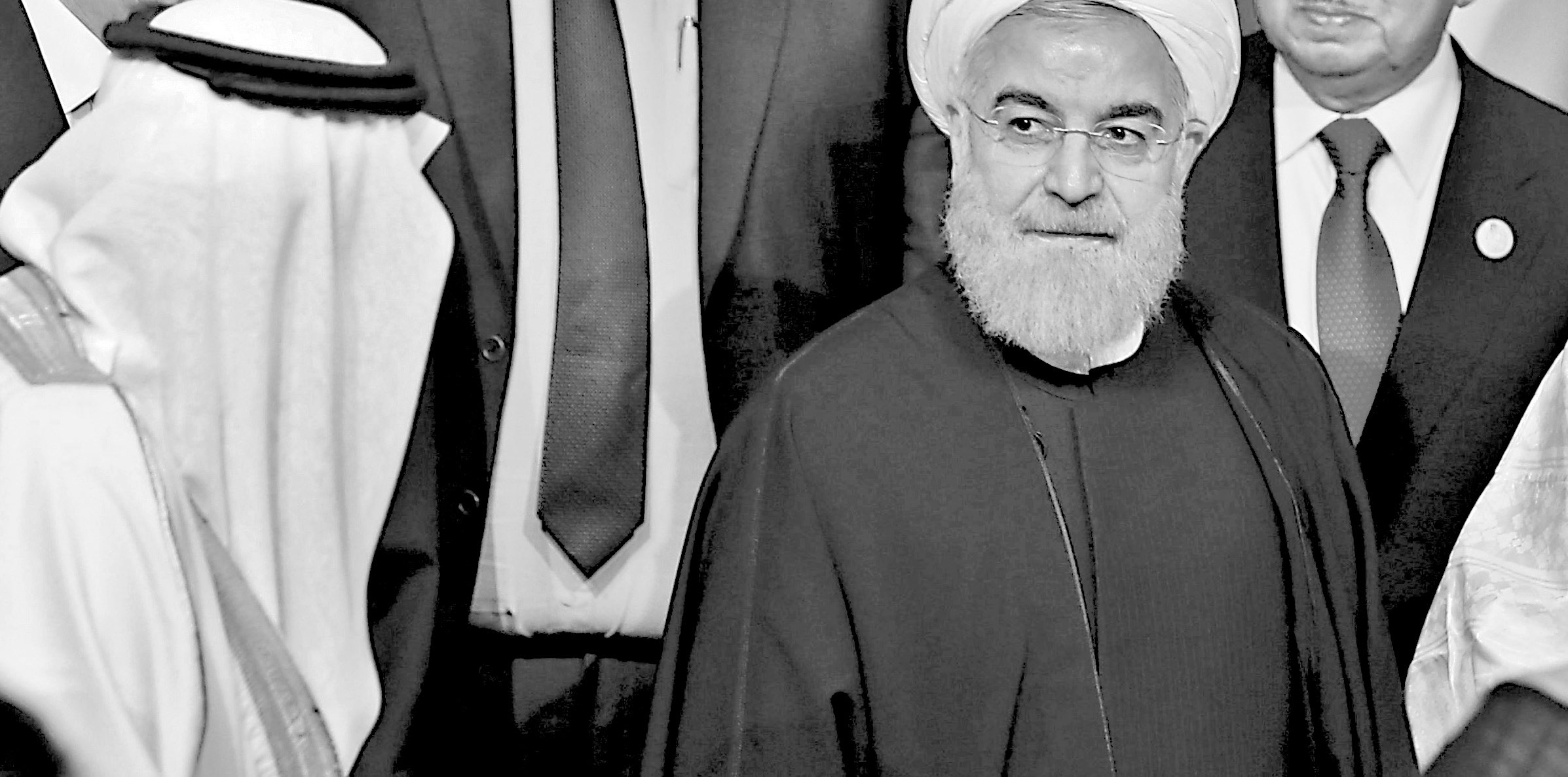

The most important engagements among the region’s principal powers are: One, four rounds of the Saudi-Iran dialogue, with indications from both sides that considerable progress has been made to address issues of mutual concern.

Two, Turkey’s outreach to Egypt and Saudi Arabia that is seeking to bridge the divide – ideological and political – that had begun seven years ago with the overthrow of the Islamist government in Cairo of Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi by the armed forces led by General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi.

Three, Iraq’s new-found status and self-confidence that has enabled it to provide the venue for the Saudi-Iran dialogue, set up with Egypt and Jordan a new tripartite regional cooperation bloc of contiguous states, and also host a conference of all regional states and the French president, Emmanuel Macron. The conference was attended by the heads of state or government of Jordan, Egypt, Qatar, the UAE and Kuwait, while Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran were represented by their foreign ministers. The conference focused on security, reconstruction, foreign investment, climate change, alongside political, economic and security partnerships in Iraq, and supporting constructive dialogue in the region.

The conference also provided the occasion for some historic interactions among the participants: Emir Tamim of Qatar met for the first time with the Egyptian president, and also with the UAE prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid. Until early January, Qatar was blockaded for a period of 43 months by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt. Iran’s newly appointed foreign minister also met with the UAE’s prime minister.

Four, over the last year, a number of Arab nations – Bahrain, the UAE and Egypt, among them -- had already begun to reach out to the Bashar al Assad government in Damascus, affirming that earlier efforts to effect regime change had been fruitless, and that, in the absence of Arab diplomatic missions in the Syrian capital, Iran had been the principal beneficiary in terms of its political and military influence in the country. Saudi Arabia has also initiated contact between intelligence chiefs.

However, the most dramatic overture, that took place on 3 October, was the phone call that King Abdullah of Jordan made to the Syrian president. The king had wanted to make this overture earlier, possibly even in 2018, but had been prevented by the Trump administration’s desire to seek a regime change in Damascus. Now, with the US’ disengagement from West Asia and its more accommodative approach towards Syria, the king has obtained the opening he wanted.

This will give Jordan the opportunity to address some of its immediate concerns with its neighbour – cross-border smuggling and revival of economic ties, while facilitating the gradual reintegration of Syria into the Arab fold. It will also allow Egypt to send its piped gas to Jordan thr

English daily published in Bengaluru & Doha

English daily published in Bengaluru & Doha