Echoes of egalitarian Harappan civilization grow louder

In the fervent discussions surrounding the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), what is seldom broached is the subject of the largely non-hierarchical nature of this Bronze Age society, a theory that is buttressed by considerable evidence.

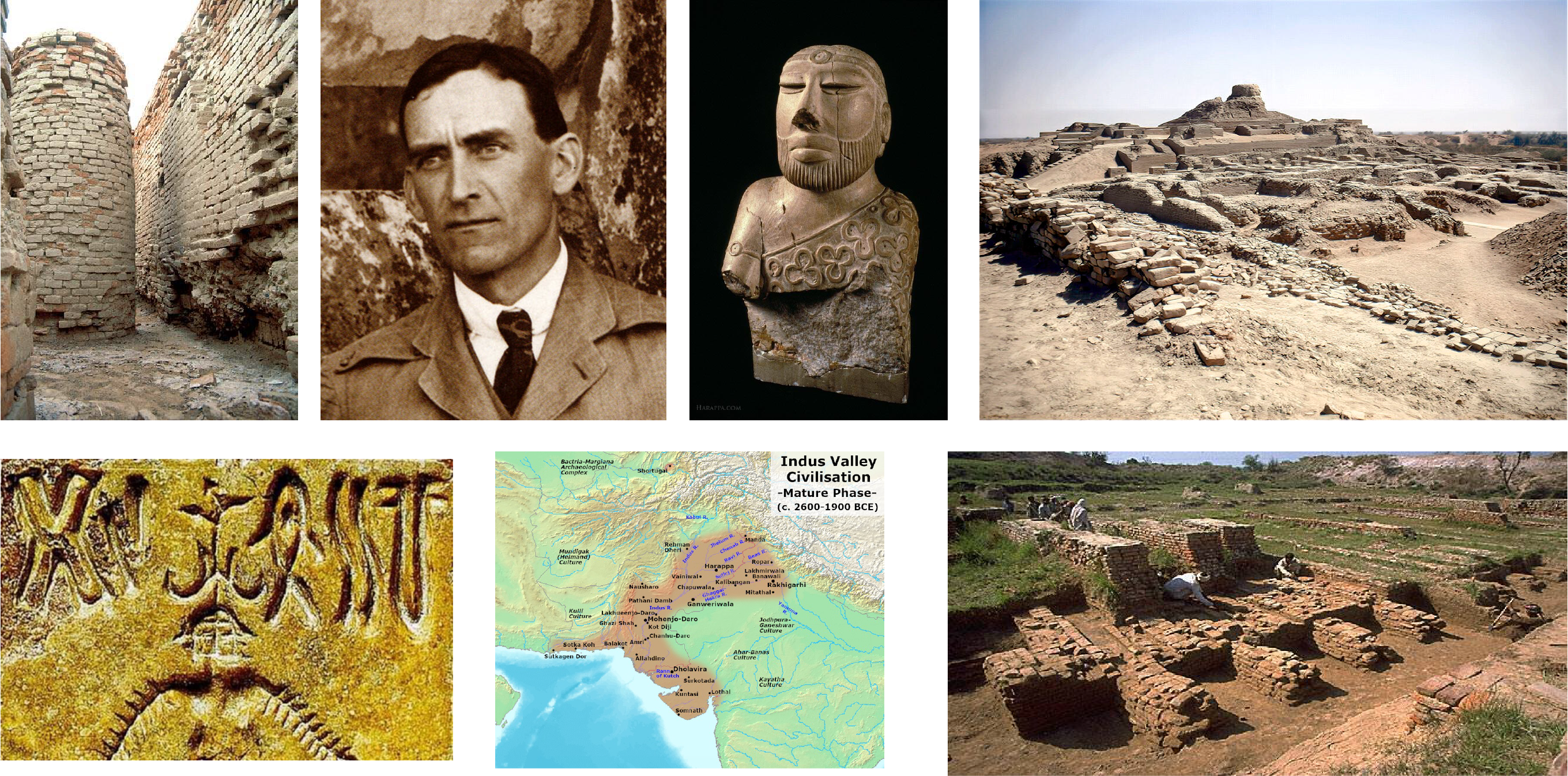

A 2020 research paper by archeologist Adam S Green entitled “Killing the Priest-King” makes a convincing case in this regard. It is argued that despite 100 years of excavations conducted at the Harappan sites, no proof of sharp hierarchies was noticed. The evidence includes the absence of monuments that glorify elites such as palaces, rich grave goods and the like.

The discussion gains prominence in the backdrop of the 100th anniversary of the appearance of Archeological Survey of India (ASI) director-general John Marshall's article “First Light on a Long-forgotten Civilisation: New Discoveries of an Unknown Prehistoric Past” in The Illustrated London News. It was published on September 20, 1924. The IVC reached its zenith between 2,600 BC and 1,900 BC and covered present-day Balochistan, Punjab and Sindh in Pakistan to Gujarat and Haryana in India.

As the story goes, archeologist Daya Ram Sahni began excavating Harappa in Pakistani Punjab in 1921. His ASI colleague Rakhal Das Banerjee also started a dig at Mohenjodaro in current day Sindh in late 1922. In April 1924, junior officer Madho Sarup Vats conveyed the feelings of Sahni and Banerjee in a letter to Marshall, pointing out the similarities between Harappa and Mohenjodaro, including identical scripts. Marshall headed the letter and thus the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilization was recognized.

No inequality unearthed

Speaking exclusively to News Trail, historian Patrick Wyman, who hosts the popular podcast “Tides of History” said unlike other contemporary civilisations in Mesopotamia and Egypt, Harappan sites didn’t yield any evidence of sharp hierarchies.

“With the evidence that is currently available to us, there is nothing to suggest the existence of sharp inequalities or a defined elite group at the top of Harappan society. Other Bronze Age civilizations have produced a great deal of obvious evidence for inequality and elite dominance: palaces, burials with rich grave goods, and skeletal remains that show differing access to food resources (i.e. unhealthy non-elites). Despite decades of searching, archaeologists have not found that kind of explicit evidence anywhere among the Harappans,” Wyman said.

The historian added researchers hadn’t determined the way in which Harappan society was organised. “Some have argued for a forerunner of the caste system or another form of group organisation that did not function hierarchically, but to be completely honest, I am not fully convinced by any of these options. We simply do not know,” he said.

Digs reveal, script conceals

Wyman conceded that deciphering the Harappan script would help in understanding the civilization better but insisted that archeological findings had explained a great deal already.

“We now know an immense amount about Harappan society, from its origins in the Neolithic period to the precise course of its disintegration in the Bronze Age. Scholars have investigated everything from the precise distribution of hundreds of settlements to the genetic ancestry of the Harappans themselves, how its internal trade networks functioned, and how it was tied to other major contemporary civilizations outside South Asia,” he said.

“While the script is undeciphered, immense amounts of archaeological evidence of various kinds tell a story without writing. It would be wonderful to have those written texts, which would surely shed light on some aspects of Harappan society, but material remains still tell us much about the nature of the period and how the people lived,” he added.

Drought spells doom

he historian also expressed confidence in new findings that the Harappan civilisation collapsed due to decades-long severe drought, which forced inhabitants to abandon major cities.

“I think there's enough evidence to say that droughts played a major role in the collapse of Harappan civilization. A series of studies over the past decade or so have looked at a number of different bodies of evidence – mineral deposits in caves, pollen samples from ancient sediments, microscopic plant remains from Harappan settlements – to track not only the severity and timing of the droughts, but also how people living at the time responded to them,” Wyman said.

“Harappans were sophisticated farmers, and they did not simply give up when droughts hit; they tried a number of different strategies to adapt to changing climatic conditions, but the droughts lasted for decades and affected such a large area that nothing worked over the long term,” he said.

Wyman added that notions of racial superiority among European scholars remained largely unchanged by discovery and exploration of Bronze Age civilisations in the subcontinent and elsewhere.

Prominent settlements litter widespread area

Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh –in present-day Pakistani Balochistan – is a kind of Neolithic (of the New Stone Age) precursor to the Harappan civilization. The settlement can be traced back to as early as 7,000 BC. Moreover, it lasted until 5,500 BC. Mehrgarh has shown evidence of hunting-gathering, farming, domestication of animals and pottery.

Harappa

Harappa, the city from which the civilization takes its name, falls in current Pakistan Punjab’s Sahiwal district. It was one of the largest urban settlements of the Bronze Age Indus Valley and housed more than 23,000 people at its peak. Harappa was home to flat-roofed brick houses and other massive buildings. The city had trade relations with far-away Elam in Iran.

Mohenjodaro

Mohenjodaro – literally the mound of death – is in Larkana district of present-day Sindh in Pakistan. It is the largest Bronze Age Indus Valley city discovered. At its zenith, the city was home to more than 40,000 people. It was founded around 2,600 BC and abandoned around 1,700 BC. Mohenjodaro has thrown up some of the most noted Harappan findings such as the “great bath” building. It has also unveiled artifacts like a stone sculpture labeled “priest-king”, the famous bronze “dancing girl” statuette. The city also traded with Mesopotamian cities.

Dholavira

Dholavira is located in Kutch district in Gujarat. It was one of the five largest cities of the Harappan civilisation. The city consisted of three parts, namely the citadel, middle and lower towns. Dholavira has thrown up important findings such as a sophisticated water conservation system in what was a largely arid region.

English daily published in Bengaluru & Doha

English daily published in Bengaluru & Doha